BLOCKHAUS

A Belgian bandit on the Blockhaus

This climb, whose name is apparently suggestive of a German scenery, is actually located almost at the very centre of Italy, nestled in the Maiella massif, in the Abruzzo region.

The name ‘Blockhaus’ – meaning ‘stone house’ in German – is thought to come from an Austrian commander who was stationed atop the mountain, where a stone fortress was standing, with a squad of riflemen to fight banditry in the early years after the Unification of Italy.

Shepherds and bandits left their names and thoughts in a large slab of rock, called the ‘Tavola dei Briganti’, which can still be seen nearby. The most famous engraving, dating back to 1867, goes “1820 marked the birth of Victor Emmanuel II, king of Italy. In the past, 60 was the kingdom of flowers. Today, it is the kingdom of sorrow”.

The Blockhaus first featured in the route of the Giro d’Italia exactly one hundred years later, on 31 May 1967, marking one of the greatest moments in the history of cycling. The hero of the day was a young man from Tielt-Winge, in the Flanders region. Aged less than 22, and on his maiden Giro, he was already twice a Milan-Sanremo winner.

The front-runners on the starting line in Caserta were José Perez (the GC leader), Anquetil, Motta, Gimondi, Adorni, Zilioli and Vito Taccone, the local idol, ‘the chamois of Abruzzo’.

Cheered upon by his people, Taccone attacked first and solo. The finish, however, was still a long way to go, so he had to give in some 13 kilometres before the summit.

As the race continued, the favourites acted strategically and cunningly, examining each other without attacking.

When Schiavon and Zilioli eventually kicked clear, 2,000 metres before the line, the stage seemed to come down to a head-to-head dash between them for the line. Most unexpectedly and much to everyone’s surprise, however, that young Belgian rider aged less than 22 counter-attacked out of the peloton.

He caught up with the attackers and jumped away just before the final kilometre. Nobody could counter his attack. He won by a 10” margin over Zilioli and over the GC leader, Rosa Perez.

That day, many said ‘Victory on the Blockhaus went to a sprinter’, as to emphasize that the ‘others’ – the climbers, the front-runners – played a waiting game.

They still didn’t know that what they had just witnessed was bound to change cycling, forever.

They still didn’t know that the young man who had just conquered the summit of the Blockhaus would eventually become the greatest rider of all time – Eddy Merckx.

MORTIROLO

Mortirolo – The rise of a warrior

Strategically located between the Val Camonica and the Valtellina, the Mortirolo Pass has been a battlefield long before June 3, 1990, when it first featured in the route of the Giro d’Italia.

Legend has it that the pass was named after a fierce battle that took place there in AD 773, when Charlemagne crossed swords with the Lombard military, which had been defeated in the battle of Pavia. The Carolingian army chased and found them by the pass, killing hundreds of enemy troops. The mountain was hence named Mortarolo (after ‘morte’, meaning ‘death’) and, centuries later, Mortirolo.

As we said, however, this is a myth.

The placename is actually thought to come from ‘mortèra’ or ‘mortarium’, two words referring to the presence of a pond, or to the concave shape of the summit of the pass.

What is not a myth is the fighting between the partigiani and the Nazi fascists that took place from February to May 1945, which many historians regard as the major field battles of the Italian Resistance movement.

The climb passed into cycling legend on June 3, 1990.

The ascent was from Edolo, and Venezuela’s Leonardo Sierra, first to the summit, eventually took the stage.

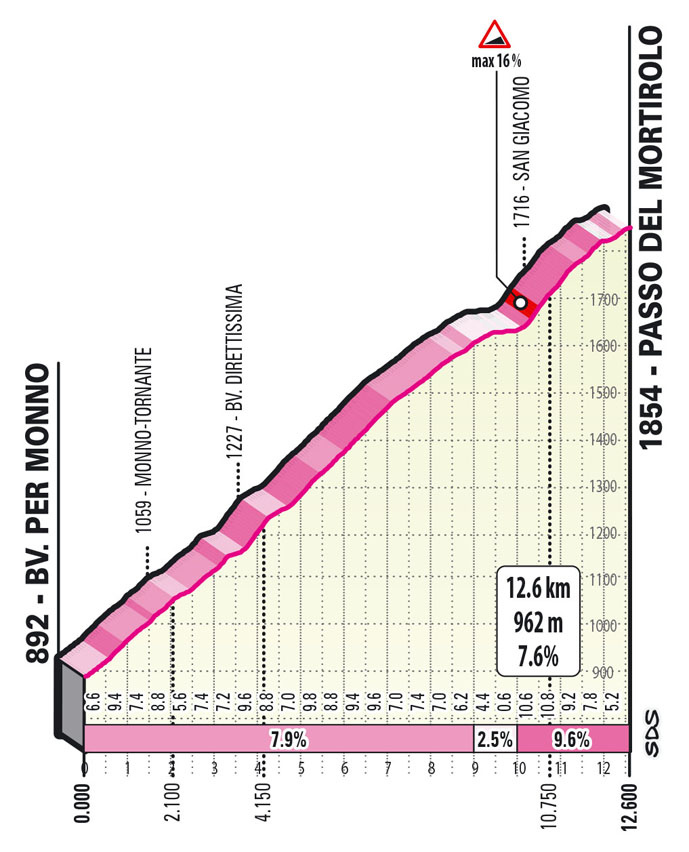

The Mortirolo was so fascinating that it was used, again, the following year, ascending from Mazzo, which became the ‘traditional’ side: 12.5 km with an average 10.5% gradient, topping out at 20%.

This is what happens to certain climbs.

Up to one day before, they are just unknown roads, lost in the middle of nowhere. Once they have been travelled, however, they immediately win the hearts of the organizers, of the riders and – above all – of the fans. That was the case with the Muro di Sormano and with the Zoncolan as well.

Then came 1994, the year when both the Mortirolo and Marco Pantani – two matching, twin stories –ultimately became legends.

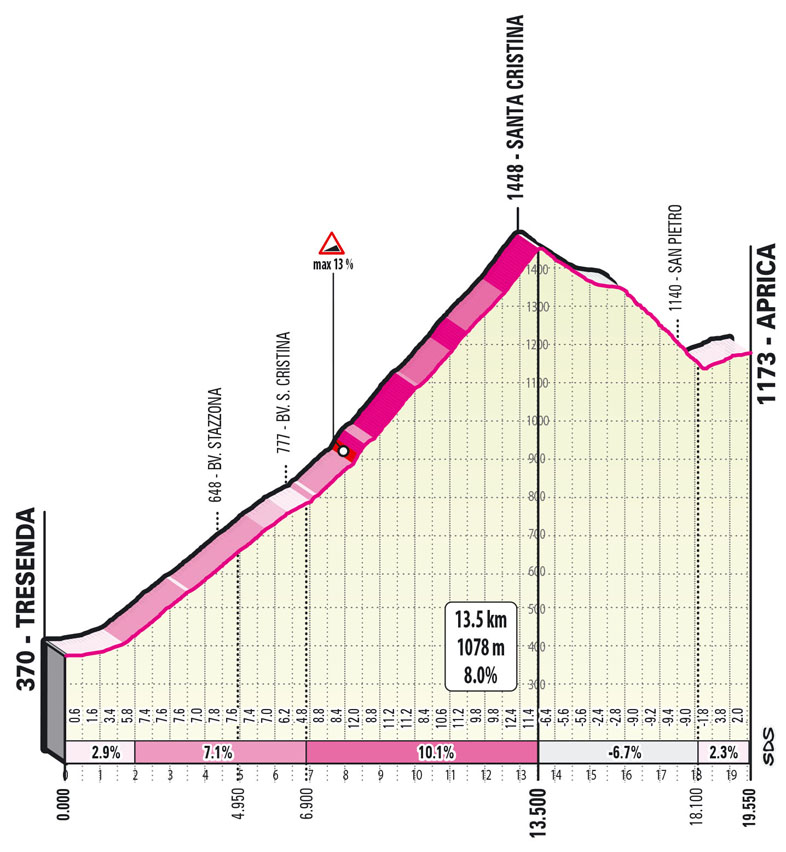

June 5 was the day of the Merano-Aprica stage, with the Stelvio, Mortirolo and Santa Cristina climbs scheduled in order.

The Pirate, who was only 24 at that time, attacked along the punishing slopes of the second climb, at over 60 kilometres out.

He dropped Indurain, Bugno, Chiappucci and the Maglia Rosa Berzin, soloing over the top. He waited for Indurain in the flat stretch before the final ascent, where he took off again – this time for good – dashing to the line to take stage victory and the second place on GC.

In 2006, a sculpture was placed at the 8th kilometre of the Mortirolo to commemorate that accomplishment. Pantani is portrayed attacking, his hands in a low grip on the handlebars, looking back at his defeated opponents.

That day, in a place that had been a battlefield for over a thousand years, the Pirate did more than just score a stage win. He found his vocation, his destiny. He found himself.

SANTA CRISTINA

Santa Cristina – The airplane and the tank

One just cannot speak of the Passo (or Valico) di Santa Cristina without also mentioning that stage, the Merano-Aprica of 1994.

On that day, this iconic climb first featured in the route of the Giro d’Italia. On that day, a young and virtually unknown Marco Pantani attacked along the Mortirolo, dropping all his strongest opponents.

In the following false flat, his team car advised him to wait for Indurain and Rodriguez. They were only a short distance away, and they could be of help before the closing climb to Santa Cristina.

So he did, and the three got along well. Moving to the fore early on the ascent, Indurain played the only card he knew he had: keeping the fastest pace he could to dissuade his young breakaway companion from attacking, or, at least, to delay any potential move as much as possible.

Looking at the footage of that climb, there is something touching and emotional in Indurain’s attempt to resist the Pirate – a completely different rider, with a completely different style.

One was a tall, sturdy, pure time trialist who was skilled enough to endure along a climb by holding a steady tempo, who was however afraid of attacks and changes of pace.

The other was a tiny little rider blown away by the wind on pan-flat roads. As soon as the gradients went up, though, when everyone else started praying for air and strong legs, to no avail, he would take flight, as if by magic.

The two were worlds apart, like a tank and an airplane.

Yet, at that very moment, early on the Santa Caterina ascent, the airplane and the tank were still riding side by side, against the laws of physics and against all logic, as if in some kind of spell (you know, cycling can work magic sometimes).

As it always happens, however, spells don’t last long, and reality kicked in powerfully after a few kilometres.

Pantani moved up to Indurain, kicked clear and never turned back.

The airplane had taken flight, quickly and lightly, and the tank had to surrender.

The gap grew with every inch of tarmac, with every switchback. At the summit, it had reached a whopping 3’19”, especially considering that it all happened in less than five kilometres.

His lead further grew in the short descent before the finish in Aprica, and the Pirate won the stage 3’30” ahead of Indurain and 4’06” ahead of the Maglia Rosa Berzin, snatching the second place on GC from the Spaniard.

So, on that epic stage, the Passo di Santa Cristina first featured in the route of the Giro d’Italia. A debut on the top-class cycling scene that we will never forget.

KOLOVRAT

Kolovrat – A sign of peace

This climb, a new acquaintance to the Giro d’Italia, culminates at 1,162 metres atop the Kolovrat, a mountain ridge in the easternmost corner of Friuli-Venezia Giulia, on the border with Slovenia.

Across the border, the ascent begins in a small village along the banks of the Isonzo called Kobarid, which is probably best known by its Italian name, Caporetto.

The Caporetto. The scene of the battle that forced the Italian troops to a long retreat to the line of the Piave River in October 1917.

In those months, the Second Army had taken the Kolovrat and turned it into a massive and complex defence system, its reliefs serving as the ultimate stronghold to prevent the enemy from penetrating into the Friuli plain.

One of the German officers who most significantly contributed to the fall of the Italian lines was the young lieutenant Erwin Rommel, who would later become known as the Desert Fox.

He launched a surprise attack on October 25, eventually taking the entire Kolovrat ridge and capturing thousands of prisoners.

In his diary, he wrote that the main clash those days was with the Italian Bersaglieri near Livek (Luico), a small hamlet south of Caporetto.

Livek will feature in the stage route halfway through the ascent, marking the only short manageable stretch out of 12 tough kilometres.

The following day, advancing from Livek, Rommel captured Mt. Matajur almost without firing a single shot.

The Friuli lowlands opened before his eyes. From there, he could easily have reached Cividale, then Udine, and who knows what else.

Instead, he was sent up north to penetrate into the Piave valley. To do this, he resorted to bicycles, which were widely used in war. Once again, he succeeded, and in his diary he wrote, “Either by horse or by bicycle, we soon caught up the first fleeing Italians. There was no need to fight. We just shouted down and told them to surrender.”

After 105 years, a cycle-mounted squad will be back up there, between Caporetto and the Kolovrat.

This time, however, there will be no armies, no military disasters and no bloodthirsty bravery, only cycling in its purest form, serving its original purpose – a popular pastime that everybody loves, a sign of peace and unity.

PASSO FEDAIA

Passo Fedaia – One of many gifts

The Giro d’Italia first tackled the Passo Fedaia on June 5, 1970.

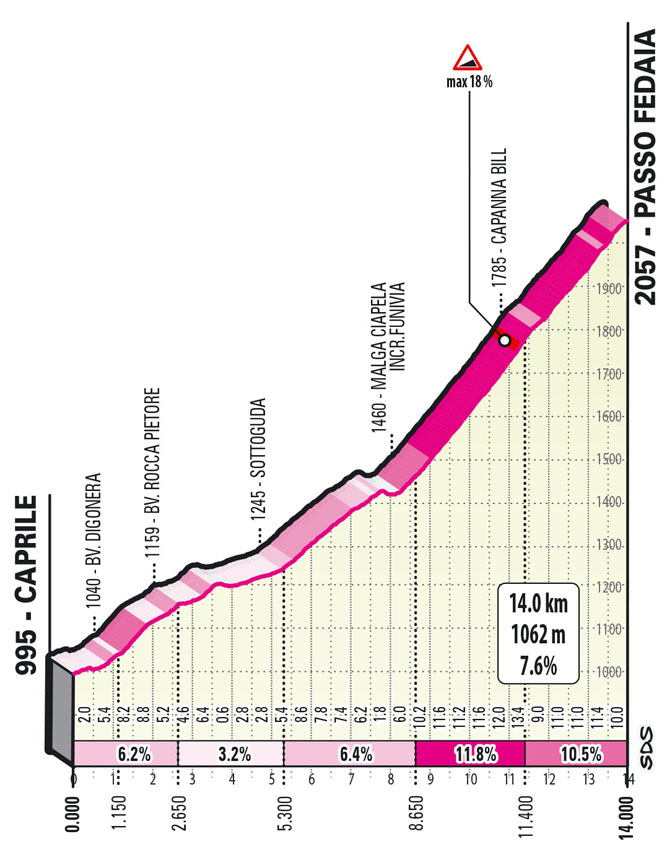

The climb was already supposed to feature in the route of the Trento-Malga Ciapela stage the previous year, but the inclement weather stopped its debut: the stage was cancelled because of snow and wind on the passes, and rain and hail in the valley.

Torriani, however – the man who had introduced the Stelvio in 1953 and the Gavia in 1960 – wasn’t going to give up on that spectacular finish at the foot of the Marmolada, the Queen of the Dolomites. The peloton came back there exactly twelve months later. It was a lovely sunny day, then.

Merckx was in the leader’s jersey. His teammate Zilioli had broken away but was eventually hauled back shortly before the line. It was a six-man battle to the finish between Gimondi, Merckx, Bitossi, Dancelli, Vandenbossche and Gösta Pettersson.

Michele Dancelli, the points classification leader, attacked at 500 metres out, storming to victory.

Curiously, though, when the Giro first tackled the Marmolada, it didn’t really climb the Passo Fedaia. The peloton indeed took on the first 9 kilometres, from Caprile to Malga Ciapela, through the stunning Serrai di Sottoguda – a narrow gulch carved by the Pettorina river – but the pass was still 5 kilometres away. The hardest, most selective and – possibly – the toughest 5,000 metres of the Dolomites.

Just past Malga Ciapela, the route takes a slight right, and then, around the bend, the climb eventually shows its hardest face. First comes a straight of nearly 3 kilometres, averaging 12% and peaking out at 16%, followed by a further 2,500 metres ascending in hairpins with double-digit gradients.

Torriani knew it well, so he decided to save that gruelling stretch for the future, as if he wanted to unveil such a wonder a bit at a time. Which he eventually did in 1975, in the second to last stage of the Giro.

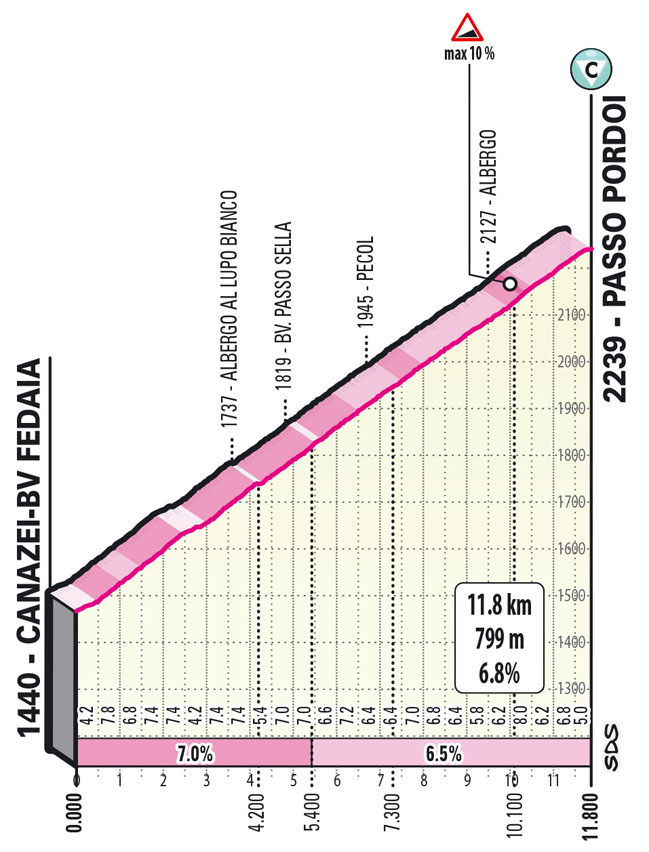

The route, from Pordenone to Alleghe, featured climbs up the Staulanza, Colle Santa Lucia, Fedaia and Pordoi passes. That day, the GC leader Fausto Bertoglio cracked along that terrible straight, however managing to defend the jersey against Galdos and De Vlaeminck, who eventually won the stage.

Special mention, though, must also be made of the powerful rouleur Giancarlo Polidori, hailing from Le Marche, and racing for Furzi. He was the first to clear the 2,057-metre Passo Fedaia. He was the first to be struck by the sight of the glacier embracing the Queen of the Dolomites all the way to the summit. He was the first to stare in wonder at one of the many great gifts from Vincenzo Torriani to the Giro d’Italia and to the entire cycling world.

PASSO PORDOI

Passo Pordoi – Alliance and rivalry.

The narrative of the Passo Pordoi is so closely entwined to that of the Giro d’Italia, and so deeply rooted in our collective memory, that it seems nearly impossible to remember when the two first met each other.

Yet, obviously, there is a date: June 5, 1940. It was Giro stage 17, from Pieve di Cadore to Ortisei.

Coppi was a rookie back then. He had set off from Milan serving as a domestique for Bartali. One stage after another, however, the two switched roles, and that day Fausto was the one in the leader’s jersey, while Gino was there to support him.

The two kicked clear together, opening a large gap behind them.

Early on the Pordoi, however, the young Coppi appeared to be in trouble. It felt as if he would rather quit, ditch his bike and jump on his team car, than face that final climb. Bartali waited for him, urged him to continue, and threw snow at him to get him back on his feet, which Coppi eventually did. Bartali cleared the climb first, eventually taking the stage, whereas Coppi staked a claim on overall victory, with help from his top-class domestique.

That scene, alone, would be enough to explain how closely tied the Pordoi is to the Corsa Rosa. Fausto’s collapse along those slopes, on the year of his first Giro win, and the birth of a relation that was bound to become the greatest rivalry in the history of cycling and beyond.

That, alone, would be enough, but many other episodes further strengthened that bond. June 12, 1947 was one of these.

The stage travelled 194 kilometres across the Dolomites from Pieve di Cadore to Trento, taking in climbs up the Falzarego and the Pordoi.

Bartali was in the leader’s jersey, and Coppi ranked second overall, 2’40” behind him.

That stage was perhaps the last chance to turn the GC.

The two kicked clear early on, as they did seven years before. By the time they reached the Falzarego, they were standing alone at the front.

Along the climb, however, Ginettaccio dropped his chain. Taking advantage of the situation, his former teammate pulled off one of his most epic and extraordinary achievements.

He cleared the Falzarego alone, gained on along the valley, and opened an unbridgeable gap on the Pordoi. He crossed the line in Trento after a 150-km solo break, 4’24” ahead of Magni, the runner‑up, and – most importantly – snatching the leader’s jersey from Bartali.

After that day, the Giro d’Italia tackled the Passo Pordoi 38 more times, including four as stage finish and 13 as Cima Coppi. The pass increasingly became a permanent fixture, a mandatory crossing point for riders and cycling enthusiasts alike, so that it seems almost impossible to recall when its legend was born. But now we know where it all came from – the alliance (and rivalry) between two of the greatest aces of Italian cycling.