An itinerary through the territory of Parmigiano Reggiano. And the Food Stage of the Giro d’Italia is dedicated to this Italian excellence.

At dawn on Wednesday 18 May, as Richard Carapaz and Vincenzo Nibali get ready to set off on stage 11 of the Giro d’Italia, more than two thousand people are already at work in the milking parlours of the farms. Within two hours, the milk is distributed to over 300 dairies, where it arrives still warm, ready to be processed together with rennet and salt, as it has been for almost a thousand years. In the meantime, the pro riders compete along the route from Sant’Arcangelo di Romagna to Reggio Emilia, the first Food Stage in the history of the Corsa Rosa, created to celebrate the indissoluble bond between Parmigiano Reggiano and its land, certified by the DOP (Protected Designation of Origin) seal. In the evening, when the champions have already got off their bikes and the spotlights are off, 10 thousand new wheels of Parmigiano Reggiano have been produced and put to rest, before being immersed in the solution of water and salt that precedes the maturing phase.

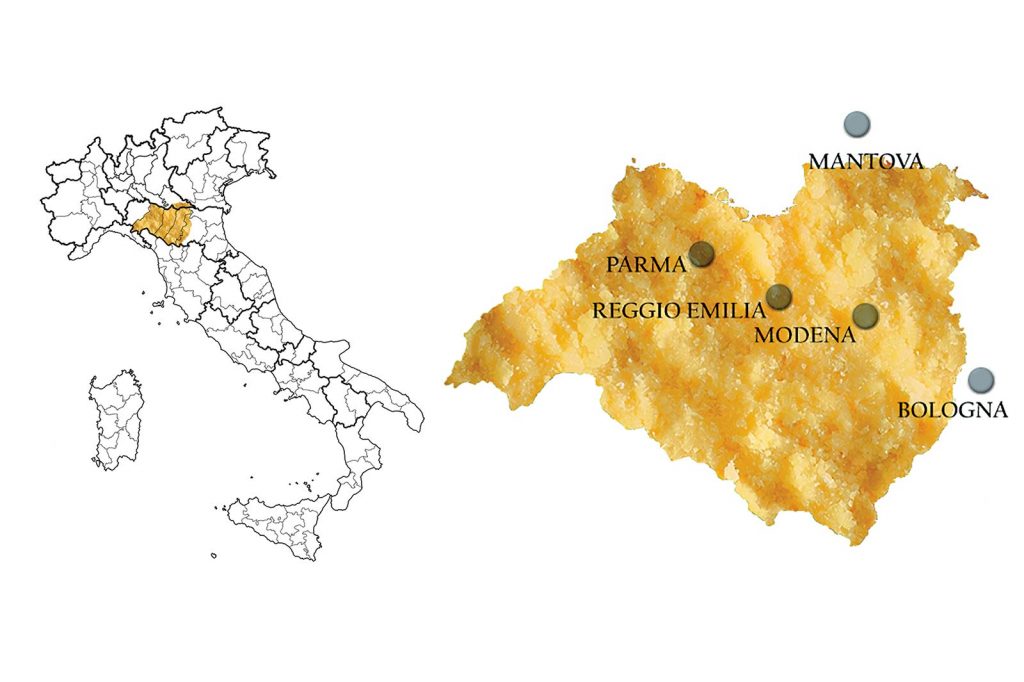

It is a ritual that follows rules laid clearly down in a strict Disciplinary Code: only raw milk, no additives or preservatives, and no bacteria selected in laboratories. And it is repeated every day in this territory between the provinces of Parma, Reggio Emilia, Modena, Mantua to the right of the river Po and Bologna to the left of the river Reno. Nowhere else in the world, even using the same production techniques and respecting the same traditions, is it possible to obtain this ancient and very rich hard cheese, perfect for feeding sportsmen. The cattle reared on these lands are only fed naturally, with mainly locally grown fodder. Many of this derive from permanent meadows, that is, fields that are self-regenerating and have never been ploughed, sometimes for centuries. What is the result? The fodder contains as many as 60-70 different varieties of grasses, which pass from the trough to the milk and cheese: depending on the microbiological mix, therefore, each cheese takes on different flavours and aromas. Parmigiano Reggiano is therefore a unique product, but never the same: on the contrary, diversity is one of its major characteristics.

Since 2013, for example, there has been a “Mountain Product” Parmigiano Reggiano with its own specific brand: 100 per cent of the milk and at least 60 per cent of the cows’ feed come from high altitudes. But there are other reasons for this wealth. The different sensitivities of the cheesemakers, for example, but also the potentially very long maturing period. In fact, the cheese ‘comes into being’ in the dairy but only becomes Parmigiano Reggiano at 12 months, when an Consortium master grader certifies the quality of the wheels, stamping the valuable Parmigiano Reggiano mark. But it can continue to ‘grow’ for a long time, taking on different flavours. Thus, while the cheese aged 12-19 month (Delicato) has a delicate scent of fresh milk, yoghurt and butter, the cheese aged 20-26 month (Armonico), more crumbly and grainy, also has notes of fresh fruit, such as banana and pineapple. The Parmigiano Reggiano aged 27-34 month (Aromatico) has hints of fresh fruit and an aroma of meat stock and spices, while the Parmigiano Reggiano aged 35-45 month (Intenso) has even stronger hints of spices and smoke.

What about the cows? They too contribute to the diversity of Parmigiano Reggiano, which relies on no less than four different breeds. When in Rome, do as the cows do, even in a restricted area like the one included in this Food Stage. The Italian Friesian, a highly productive breed that arrived in Italy at the end of the 19th century from the Friesland region of the Netherlands, is almost everywhere. As we pass Carpi, the bells of the Modenese white cow ring out – a Slow Food presidium whose milk, given the optimal ratio between fat and protein content and the high concentration of casein, is perfect for cheese-making. Around the finish line of Reggio Emilia is the realm of the red cow from Reggio Emilia; its milk is extremely rich in protein, calcium and phosphorus – a boon for cheesemakers because it coagulates quickly, has a consistent and elastic curd, a clear serum and a cream that surfaces perfectly. Milk from the brown cow, on the other hand, is richer in fat and casein. Would you have ever guessed that such a vast world is hidden behind shredded Parmigiano?